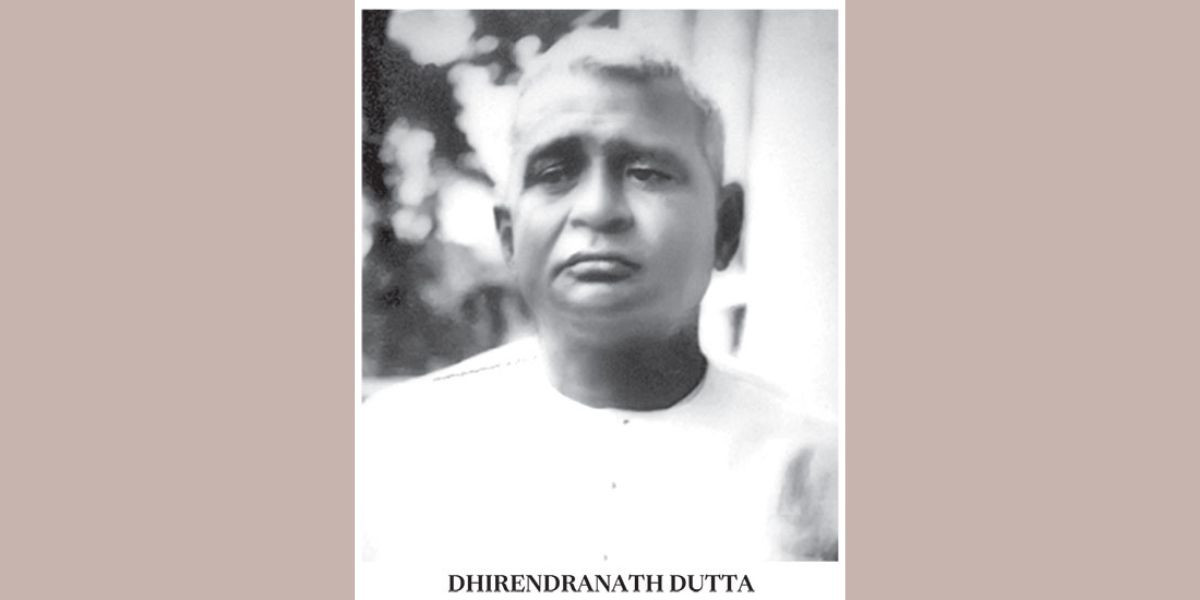

In Bangladesh’s history, Dhirendranath Dutta will forever be a revered name, for all the right reasons. We lost him to the predatory instincts of the Pakistan occupation army in 1971. His remains, as also those of his young son, were never found. It was intense torture Dutta and his child were subjected to, a crime for which his murderers were never called to account.

Dutta is one of our authentic national heroes. It was he who first rose in defence of the Bengali language in Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly. Recall his statement on the floor of the House on 25 February 1948: "But, Sir, if English can have an honoured place in Rule 29 --- that the proceedings of the Assembly should be conducted in Urdu or English --- why Bengali, which is spoken by four crores forty lakhs of people, should not have an honoured place, Sir, in Rule 29 of the Procedure Rules? So, Sir, I know I am voicing the sentiments of the vast millions of our state and, therefore, Bengali should not be treated as a provincial language. It should be treated

An irascible Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan’s Prime Minister, lost little time in shooting down Dutta’s statement: "He should realise that Pakistan has been created because of the demand of a hundred million Muslims in this subcontinent and the language of a hundred million Muslims is Urdu . . . Pakistan is a Muslim state and it must have as its lingua franca the language of the Muslim nation. . . The object of this amendment is to create a rift between the people of Pakistan. The object of this amendment is to take away from the Mussulmans that unifying force that brings them together."

But Liaquat’s words did not go unanswered. It was Bhupendra Kumar Datta, another Bengali member of the assembly, who responded to the Prime Minister: "Urdu is not the language of any of the provinces constituting the Dominion of Pakistan. It is the language of the upper few of Western Pakistan. The opposition to the amendment proves an effort, a determined effort, on the part of the upper few of Western Pakistan at dominating the state of Pakistan."

Now notice the audacity with which a non-Bengali member, Ghazanfar Ali Khan, attempted a denigration of Bengali:

"I am sure the Bengal government realise their responsibility and they will take immediate steps to popularise Urdu in the schools, so that after a period of ten or fifteen years there may not be a single Bengali who will not be well conversant with the national language of the state."

And now observe Khwaja Nazimuddin, who would become Pakistan’s Governor General after Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s death and Prime Minister after Liaquat Ali Khan’s assassination, make a misleading statement on the language issue:

"Sir, I feel it my duty to let the House know what the opinion of the overwhelming majority of the people of Eastern Pakistan over this question of Bengali language is. I think there will be no contradiction if I say that as far as inter-communication between the provinces and the centre is concerned, they feel that Urdu is the only language that can be adopted."

In Dhirendranath Dutta was the soul of a thorough political being. There were in him all those traits which went into the making of a man of strong intellectual and moral fibre. In him were all those hallmarks of personality which went into his emergence as a leader. He was astute enough to comprehend the realities that would define for Bengalis their world of the future. The Language Movement we commemorate annually is but a mark of the presence of Dhirendranath Dutta in our collective life, for it was he who first instilled in us the sentiments associated with a heritage which needed to be reaffirmed in us despite our being part of Pakistan.

The moral force in Dutta’s defence of the Bengali language on 25 February 1948 said it all: "I know, Sir, that Bengali is a provincial language, but, so far as our state is concerned, it is the language of the majority of the people of the state. So although it is a provincial language … it is a language of the majority of the people of the state and it stands on a different footing therefore. Out of six crores and ninety lakhs of people inhabiting this state, four crores and forty lakhs of people speak the Bengali language. So, Sir, what should be the language of the state? The language of the state should be the language which is used by the majority of the people of the state, and for that, Sir, I consider that the Bengali language is a lingua franca of our state."

It remains a matter of shame that not a single Muslim Bengali member of the Constituent Assembly could call forth the wisdom to support Dutta on that day. Not one Muslim politician rose in that chamber to support Dutta, to speak for their land. Their loyalty to the Muslim League proved to be deeper than their concern for their language and for their distinctive cultural heritage.

In the House on that day, Dutta’s demand that the proceedings of the assembly be enlarged to accommodate the Bengali language, to allow the poverty-driven peasant in Bengal to communicate better, in his native language, with his child pursuing education in urban circumstances, met with derision from Liaquat Ali Khan and other West Pakistani politicians. They spotted, incongruously, in Dutta’s statement the seeds of conspiracy. The conspiracy theme was to be the weapon the entrenched Pakistani political leadership would employ every time Bengalis demanded their political and economic rights in the twenty-three years in which Bangladesh was part of Pakistan. The bitterness thus engendered would lead to the collapse of Pakistan in 1971.

Like so many others, Dutta could have moved to India in the aftermath of Partition in 1947. But he chose to stay on in his beloved Comilla, in East Bengal. Patriotism defined him. As a Hindu he was in danger in communal Pakistan, but that unnerved him not at all. Having struggled for an end to British colonial rule, Dutta focused on the need for democracy in the improbable state of Pakistan. As part of the short-lived Jukto Front ministry in 1954, he proved, along with other men of liberal intent, that politics could return to being secular among the Bengalis, indeed that the "two-nation theory" was not just an aberration but an abomination as well. The state of Pakistan, determined to crush Bengali nationalism in 1971, went after Dhirendranath Dutta in the early stages of the genocide in March. The eighty-five year-old politician and his son Dilip Dutta sere picked up by the soldiers, never to be seen again.

It was courage of conviction on which Dhirendranath Dutta conducted his political principles. That was his greatness. That was his wisdom. In this month of February, as we recall the 1952 Language Movement, we inform ourselves that in February 1948 it was Dhirendranath Dutta who set East Bengal on a course that would lead eventually to the emergence of a sovereign Bangladesh in 1971.

Syed Badrul Ahsan writes on politics, diplomacy, history