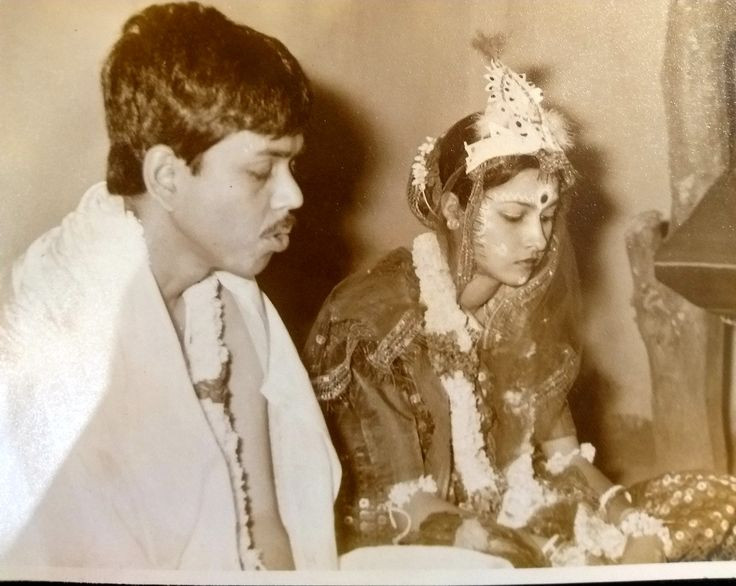

A 150-year journey through Bengali matrimony

In both Hindu and Muslim communities, marriages were rarely based on love or personal choice.

Nahida Sultana Sayma

Published: 16 Jul 2025

Photo: Pinterest

For centuries, marriage in Bengali society has been more than a personal bond—it’s been a mirror of social, religious, and cultural hierarchies. Though no radical deviation from broader Indian matrimonial practices is evident in Bengal’s earliest history, the region’s customs gradually took a distinct form influenced by a tapestry of local traditions, religious reforms, colonial encounters, and ultimately, modern education.

Marriage rituals among Bengalis were shaped initially by Vedic and Buddhist traditions and further molded by Islamic cultural integration during Muslim rule. Practices like applying turmeric paste on the bride—still seen today—reflect local flavors that endured despite changing political and religious landscapes. Interestingly, while Muslim conquerors often married local Hindu women, this did not fundamentally alter the concept of marriage as a patriarchal and duty-bound institution.

In both Hindu and Muslim communities, marriages were rarely based on love or personal choice. Romantic preferences were not just discouraged but often irrelevant. The age of marriage was shockingly low—girls were often wed before the age of ten, with extreme cases of marriage involving toddlers. The practice was defended using religious scriptures, with texts like Manusamhita suggesting eternal damnation for parents who allowed daughters to reach puberty unmarried.

Widowhood, naturally, was a tragic and frequent consequence. Since child mortality rates were high, many young girls lost their husbands early and were then sentenced to a life of social exclusion and deprivation. Hinduism’s rigid opposition to widow remarriage made this tragedy even more harrowing. Muslim society, by contrast, was more accepting of widow remarriage, though women’s consent was rarely a priority.

Polygamy was another normalized facet of marriage. Among both rich Hindus and Muslims, multiple wives signified wealth and status. Kulin Brahmins took this to an extreme—some reportedly had over 100 marriages—mostly for financial gain and social prestige. The practice often reduced marriage to a commercial transaction, where status outweighed emotional or personal compatibility.

The colonial period brought new disruptions. With the spread of English education, marriage customs began to shift. As men pursued university degrees and government jobs, their age of marriage naturally increased. Yet, girls remained trapped in early marriages, creating a stark age gap and reinforcing gender imbalances in marital dynamics. Educated men, now influenced by Western ideals, started seeking more emotionally responsive partners—but women were seldom given the same liberty to choose.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw isolated but notable incidents of interfaith and intercaste marriages, mostly among reformist groups like the Brahmo Samaj. The 1872 Civil Marriage Act opened legal space for such unions, but social stigma was still immense. Figures like Atulprasad Sen, who married his cousin in Scotland due to legal constraints in England, symbolized the tension between personal choice and societal restrictions.

Even Rabindranath Tagore, the icon of Bengali modernism, was not immune to convention. He married an illiterate eleven-year-old girl at 23. Yet, in his literature, we see the early glimmers of change. Characters like Gora’s Sucharita or Hoimonti’s tragic protagonist reflected young women with individual agency and emotional complexity—unlike the voiceless brides of traditional tales.

Photo courtesy: Columbia blogs

The dowry system, one of the most destructive social norms, continued to flourish across religious and class lines. Sons were assets, daughters financial burdens. Parents often went into debt or sold property to marry off daughters with sufficient dowry. Even Tagore reportedly had conflicts with his sons-in-law over dowry demands. Though modern dowry increasingly takes the form of consumer goods rather than cash, the coercive structure remains intact, especially among poorer families.

Interfaith marriages remained rare, and Hindu-Muslim unions, particularly those involving Hindu grooms and Muslim brides, were almost unheard of until the 20th century. While a few historical examples exist—most famously the marriage of poet Kazi Nazrul Islam to Hindu woman Pramila Sen—they remained exceptions that triggered considerable controversy.

By the mid-20th century, societal changes were more visible. Women’s education improved, albeit slowly, and their participation in public life grew. Romantic love gained legitimacy, and personal compatibility began to enter the conversation on marriage. However, patriarchy retained its stronghold. Divorce, though more common, still bore a deep stigma, especially for women. Men could remarry with ease, while divorced or widowed women were seen as damaged and unfit for new marriages.

The post-independence decades further diversified Bengali marital customs. Economic mobility, media exposure, urbanization, and women’s entry into the workforce gradually altered perceptions of ideal spouses. Traits like education, income, and personal freedom began to trump caste, lineage, and even religious purity in some segments of society. Yet the dual burden of tradition and modernity persisted. Girls were expected to be educated but not too assertive, desirable but submissive.

Photo courtesy: MyWed

Today, Bengali marriages reflect a fascinating contradiction: the rising tide of love marriages, coexisting with enduring dowry demands and parental dominance. Divorce rates are increasing, suggesting a new willingness to prioritize personal well-being over social optics. At the same time, women still face greater societal scrutiny in cases of marital breakdown. Remarriage remains easier for men, and the notion of “purity” continues to influence female worth in the marriage market.

In sum, marriage in Bengali society has evolved from a rigid social contract governed by caste, custom, and control into a more fluid institution shaped by individual desires, education, and emotional compatibility. Yet the journey is far from over. The slow dismantling of patriarchal structures reveals both progress and persistence of old values.

What remains clear is that Bengali marriage is no longer just a familial obligation—it is increasingly a negotiation between tradition and transformation.

Note: Information for this feature has been drawn from various historical and cultural sources, including “Hazar Bochorer Bangalir Sangskriti” by Goulam Murshid.