M MUNIR HOSSAIN

It was a Friday morning in August 2023 when I walked into the local kitchen market near my home in Pirgachha, a small upazila town in Rangpur. Curious about prices, I asked a vendor how much tomatoes were selling for. “Tk360 per kilo,” he said. I was stunned – just a week earlier I had paid Tk250 for the same tomatoes in Dhaka.

The vendor explained that these were “summer tomatoes” from Chuadanga and Meherpur, sent directly from farms to big city arats (wholesale hubs). From there, the produce changed hands several times before finally reaching small-town retailers like him. Every step in the chain added a markup. Retailers in Dhaka, meanwhile, could buy straight from the arats, cutting out middlemen and keeping their prices lower.

He also mentioned that only a few weeks before, tomatoes had sold for as high as Tk500 a kilo because local supply had dropped and imports were limited due to government curbs linked to the ongoing dollar shortage. As a regular shopper, I knew tomato prices had reached absurd levels that year – but I didn’t expect the same produce to cost more in a rural market than in the capital. Soon I realised that this odd price pattern extended to many other fruits and vegetables too, especially those that came from distant districts or across the border.

The farmer’s frustration

That conversation took me back to an afternoon in March 2023, when I watched a man dumping baskets of ripe tomatoes into a roadside ditch near my village. His name was Sohrab, a small farmer from a nearby hamlet. When I asked what had gone wrong, he sighed and said he had taken two maunds (about 80 kilograms) of tomatoes to the arat in Pirgachha, only to find buyers offering Tk80 per maund. The arat fee alone was Tk40.

He, his wife, and his son had spent hours harvesting and sorting the tomatoes before carrying them to the market on his bicycle. After waiting three more hours for a fair deal, he gave up. There were simply too many tomatoes and too few buyers. “I can’t take them home,” he said. “They’ll rot by tomorrow. If prices don’t improve, I’ll have to leave the rest of the crop in the field.”

When I asked if cold storage might have helped, Sohrab’s reply was immediate. “Of course it would,” he said. “If we could keep tomatoes for just two or three weeks, we could sell later at better prices. Then buyers could also find them cheaper in the off-season. But here, we can only store potatoes. Nothing else.”

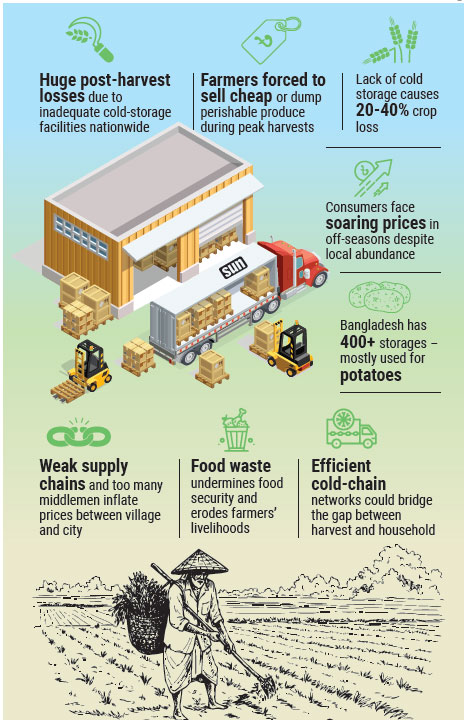

His story is shared by thousands of small farmers across the country. Every harvest season, mountains of vegetables are wasted because there are no proper facilities to preserve them. Farmers lose income, consumers face unstable prices, and the national economy absorbs the loss.

A bumper crop, yet rising onion prices

The same problem is evident with onions, a kitchen staple that often makes headlines for its wild price swings. Last season saw Bangladesh’s highest ever onion production – around 42 lakh tonnes, according to the Department of Agricultural Extension. This should have been enough to meet national demand, which stands at roughly 26 lakh tonnes. Yet by August this year, prices in Dhaka markets had soared to Tk75-85 per kilo, compared with Tk40–50 the previous season.

Farmers in the northern districts harvested their onions between February and April, the usual peak season. But most of them were forced to sell immediately because they had no way to store the bulbs safely beyond a few weeks. Reports from the Bangladesh Trade and Tariff Commission suggest that 20-25% of the local onion crop is lost each year after harvest due to poor storage and handling. The result is painfully predictable – despite record yields, the country still imports several lakh tonnes every year to make up for what rots.

Experts point out that opportunistic traders exploit this weak link in the supply chain. When the stored stock spoils or runs out, prices shoot up, and middlemen pocket the profit while both farmers and consumers lose.

The cost of waste

The loss goes well beyond onions. According to the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Bangladesh loses roughly 34% of its total food output every year through post-harvest wastage – equivalent to about four% of the country’s GDP. Fruits and vegetables alone account for a large share of this, with losses ranging between 20 and 40% depending on the crop.

At present, Bangladesh has just over 400 cold-storage facilities, and almost all of them are used exclusively for potatoes. A few are used for imported fruits or spices, but there are hardly any options for vegetables like tomatoes, beans, or carrots. As a result, the supply of fresh produce fluctuates sharply between winter and summer. Data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics show that winter vegetable output reaches around 1.3 crore tonnes, but summer production drops to barely 15 lakh tonnes. The gap leaves markets volatile and consumers vulnerable.

Some progress, but too little

In early 2025, the government announced plans to build 100 small cold-storage units across the country for seasonal vegetables, along with 500 special onion-drying houses in the 2025–26 fiscal year. Later that year, a few farmer groups in Rajshahi and Bogura received mini cold-storage systems that can hold up to 10 tonnes of vegetables each. These solar-powered units, funded by the Climate Change Trust, are expected to cut storage costs by nearly 70%.

Such steps are encouraging but remain far from enough. For a country producing tens of millions of tonnes of perishable crops every year, this handful of pilot projects cannot plug the gap. Large-scale investment, both public and private, is needed to build a proper cold-chain network – from rural production zones to urban retail markets.

The way forward

Farmers like Sohrab deserve more than sympathy. They need infrastructure that allows them to store, transport, and sell their produce without fear of ruin. The government’s recent initiatives are a step in the right direction, but they must be scaled up rapidly. Investments in small-scale, affordable storage for perishable crops could transform rural livelihoods.

Reforming the marketing chain is just as important. Reducing the number of middlemen between farmer and retailer would make prices more transparent and stable. Coupled with basic processing facilities in rural areas, such as tomato paste or dried onion units, farmers could earn more and Bangladesh could save the foreign currency it spends on importing processed foods.

Two years after I first paid Tk360 a kilo for tomatoes in a village market, the situation on the ground has not changed much. The same pattern repeats: bumper harvests followed by waste, shortages followed by price spikes. Bangladesh has proved that it can grow enough food. Now it must learn to keep that food safe after harvest. Building a reliable cold-storage network – one that connects farmers’ fields to consumers’ kitchens – would be the single biggest step toward ending this cycle of loss and imbalance.

Until then, both the hands that grow our food and the mouths that depend on it will continue to pay the price for what the country fails to preserve.

__________________________________

M Munir Hossain is Deputy Editor of the Daily Sun. Email: